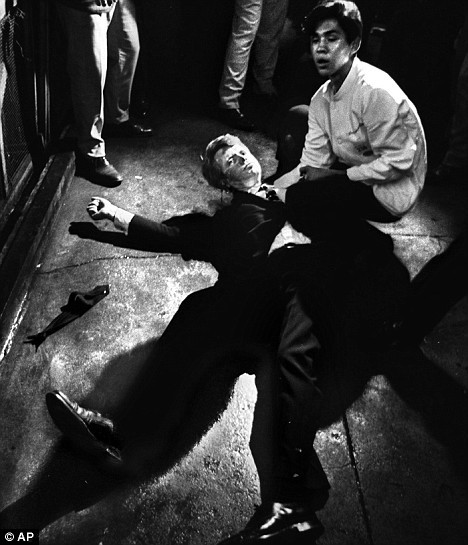

As we acknowledge the 50th anniversary of RFK’s assassination this week on June 5th, 1968, and a mere 5 months before my own birth! For me, it’s the haunting, compelling image below that captures BOTH the heartbreak and hope of the Kennedy legacy. It is forever etched in my mind every time I think of RFK, and the enduring thought of “what might have been.”

Moxie stunted by an assassin’s bullet.

Robert F. Kennedy, moments after being struck by an assassin’s bullets, lies broken and bleeding on the floor of a hotel kitchen. While others gather around, paralyzed in shock and fear, a busboy named Juan Romero cradles him gently, his eyes filled with grief and horror, a plea for help etched across his face.

In the last conscious moments of his life, the scion of a wealthy and influential East Coast family was comforted by a 17-year-old working-class boy who had immigrated to the United States from Mexico just a few years before.

“Is everyone OK?” Kennedy whispered to Romero. Romero assured him everyone was ok, even as he felt Kennedy’s blood seeping through his own fingers as he cradled his head to keep it off the hard concrete of the kitchen floor.

It was the same hand that had been gripping Kennedy’s hand just moments before. The assassin had reached across Romero’s shoulder as he shook Kennedy’s hand, firing as the presidential candidate paused to greet kitchen staff after winning the California primary.

It was a stunning blow. Kennedy’s moxie inspired the young, the poor and the disenfranchised. How does an East Coast elite not only relate but actually lead a movement championing social justice? Here are a few clues to RFK’s moxie:

Sometimes moxie is the runt of the litter.

Bobby was the seventh child born to Joe and Rose Kennedy, and the third boy. His father had big aspirations for his children and began grooming them for lives of greatness from the time they were toddlers.

Except maybe Bobby. Joe dubbed him the “runt” of the litter, and was dismayed by the boy’s gentle demeanor. He was especially close to his mother, and grew to most genuinely share her Roman Catholic convictions.

For the most part, his father overlooked Bobby, and focused his attentions on preparing older sons Joe Jr. and John for leadership. Even so, Bobby worked hard to gain the attention and approval of his father and his older brothers.

“When you come from that far down, you have to struggle to survive,” he said. Perhaps it was his experiences in the Kennedy family hierarchy that gave him compassion for those overlooked and ignored by society.

Moxie doesn’t always quarterback.

As older brother John rose to prominence as a senator and later the president, Bobby found his place. He became the tough, hard-nosed attorney general who went after the Teamsters Union and organized crime while also championing civil rights causes. He served as his brother the president’s closest confidant and most trusted adviser.

Bobby’s blocking and tackling furthered Jack’s agenda as president. His decisions and actions were sometimes controversial, but the once-gentle momma’s boy had developed an armored hide. Far from shrinking in his older brother’s shadow, he emerged as a shield-bearer.

It wasn’t until after his brother’s death that Bobby sought his own elected office, serving as a U.S. Senator. As the nation began wading into the debate over the brewing war in Vietnam, he felt compelled to lead the charge against engaging in the war. He threw his hat into the ring, announcing his run against his brother’s successor, Lyndon Johnson, for the Democratic nomination.

The assassin’s bullet cut short his run, and he never had the opportunity to lead the country as president. However, his impact as a cabinet member and senator was significant. People with moxie don’t always have to be number one to make a difference.

Moxie runs on faith.

Bobby was especially close to his mother, Rose, a devout woman who wanted her children to adopt a sincere, genuine practice of the faith. She saw that prayer answered in Bobby, who practiced faithfully throughout his life.

He often cited his faith as the defining influence in his worldview, particularly civil rights.

“What if we go to Heaven and we, all our lives, have treated the Negro as an inferior, and God is there, and we look up and He is not white? What then is our response?” he once asked.

People with moxie don’t just attend worship services and leave it there. They study, consider, and make changes to their thoughts and actions that reflect the faith they profess.

Kennedy didn’t see others as the “less fortunate” that he, from his lofty position, might stoop to help. He saw them as equally created in the image of God, and it was his passionate conviction that he should do all he could to restore them to their rightful place.

I suppose that’s why I find it so tragic and yet beautiful that his final moments were spent cradled in the hands of a young working-class immigrant. The moment is a complicated tapestry of power, and vulnerability and humanity.

‘Everything’s going to be ok’

As he hovered between life and death on that hotel floor, Kennedy murmured “Everything’s going to be ok.” Among his last words on this earth were words of peace, reassurance, comfort. How fitting.

What words would you want to be your last? If you could choose your final message to the world, what would it be?